Ukraine and Poland : historical and modern link between

Université Grenoble (UGA)

Grenoble IAE – Gaduate school of management

Mobility Study dissertation

Licence – mobilité études Program Management 2021 – 2022

The impact of the Russian-Ukrainian war on Poland

Presented by:

FARAG Noureldin

University Advisor:

Mrs. Ludivine chaze-magnan

Host organization:

Warsaw School of Economics

Date: from 12/02/2022 to 22/06/2022

Grenoble IAE – Ecole publique de management

Grenoble INP – UGA

Disclaimer:

Grenoble IAE, University Grenoble Alpes, does not validate the opinions expressed in theses of masters in alternance candidates; these opinions are considered those of their author.

In accordance with organizations’ information confidentiality regulations, possible distribution

is under the sole responsibility of the author and cannot be done without their permission

Anti-plagiarism statement

SUMMARY

The war in Ukraine is a current topic, but it is also a problem that refers to the past. In this thesis, we will see how the war in Ukraine happened. Then we will explain the impact of this war on Poland and its operating system.

We will study the phenomenon of Ukrainian immigration to Poland and the consequences thereof. We will explain how the integration of Ukrainians took place in Poland. In addition, we will also discuss the links between Poland and Ukraine that have existed for centuries.

This thesis draws parallels between what is happening today and what happened in the past. Poland plays a major role in the handling of Ukrainian refugees; you will understand why by reading this thesis.

The objective is to understand what the stakes of such an event for Poland are, both from the point of view of its alliance with Ukraine and from the global point of view, of its relationship with European countries and Russia.

The results presented are evidence from recent sources: the invasion of Ukraine took place in February and this brief will be published in June. The study of the situation is therefore based on recent data, which will surely be specified in the future.

Résumé

La guerre en Ukraine est un sujet d’actualité mais c’est aussi un problème qui fait référence au passé. Dans ce mémoire nous allons voir comment la guerre en Ukraine s’est déclenchée.

Puis nous allons expliquer les conséquences de cette guerre sur la Pologne et son système de fonctionnement. Nous étudierons le phénomène d’immigration des Ukrainiens vers la Pologne et les conséquences qui en découlent.

Nous expliquerons comment l’intégration des Ukrainiens s’est faite en Pologne. De plus, nous évoquerons aussi les liens existants entre la Pologne et l’Ukraine depuis des siècles.

Ce mémoire fait donc les parallèles de ce qui passe aujourd’hui avec les événements historiques passés. La Pologne joue un rôle majeur dans la prise en charge des réfugiés Ukrainiens, vous comprendrez pourquoi en lisant ce mémoire.

L’objectif est de comprendre quels sont les enjeux d’un tel évènement pour la Pologne, tant au point de vue alliance avec l’Ukraine qu’au point de vue mondial, dans sa relation avec les pays européen et la Russie.

Les résultats présentés sont les éléments de sources récentes : l’invasion en Ukraine s’est déroulée en février et ce mémoire sera publié en juin. L’étude de la situation se base donc sur de récentes données, qui seront sûrement précisées dans le futur.

KEYWORDS : Guerre, Ukraine, Pologne, Immigration, Intégration / War, Ukraine, Poland, Immigration, Intégration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

First, I would like to express my gratitude to my tutor for this thesis, Mrs Ludivine Chaze-Magnan, for her patience, her availability and especially her judicious advice, which contributed to refeeding my reflection.

I would also like to express my sincere thanks to the teaching and administrative staff of the IAE of Grenoble, for the richness and quality of their teaching and who deploy great efforts to ensure their students an updated training.

I would also like to thank the professors of Grenoble IAE and the Warsaw School of Economics (SGH), who provided me with the necessary tools to succeed in my academic studies. Special thanks to Kamil KRAJ, who explain to me the economic effects in Poland during the war.

A big recognition to my mother and father, for their love, advice and unconditional support, both moral and economic, which allowed me to achieve the studies I wanted and consequently this thesis.

I would also like to express my gratitude to my girlfriend who gave me her moral and intellectual support throughout my process.

Lire aussi : La mémoire collective : définition et instrument politique

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

HISTORICAL AND MODERN LINK BETWEEN UKRAINE AND POLAND

CHAPTER 1 – BEFORE THE WORLD WAR

CHAPTER 2 – INTERWAR PERIOD UNTIL SECOND WORLD WAR

CHAPTER 3 – SECOND WORLD WAR PERIOD

CHAPTER 4 – THE CURRENT INTER-COUNTRY RELATIONS

ORIGINS OF THE WAR IN UKRAINE

CHAPTER 5 INTERNATIONAL TENSIONS

CHAPTER 6 – POST SECOND WORLD WAR MANAGEMENT

CHAPTER 7 – INDEPENDENT UKRAINE

PART ECONOMICS AND SOCIALS CONSEQUENCES FOR POLAND

CHAPTER 8 – ECONOMICS CONSEQUENCES

CHAPTER 9 – CONSEQUENCES ON THE HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

CHAPTER 10 – SOLUTIONS

CONCLUSION

INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of the Ukraine war, multiple consequences lead Poland to take important decisions. The inflation hit the country very brutally. The gas provided was cut off by Moscow and the immigration suddenly increased.

In the last ten years, it has become clear that Ukraine wants to integrate further with the West, while the Russian Federation was facing an increased number of external and internal issues from demographics through energy transition in Europe to lowering living standards.

After the pandemic, the USA and European countries were hit with inflation and disturbed by internal challenges and polarization were believed by Kremlin to be weak and not determined to respond.

Russia decided to challenge the existing order and ask to revise the security architecture in Central and Eastern Europe that began at the end of the Cold War and enabled the region to flourish economically. With NATO countries not agreeing to unfounded Russian demands, Putin decided to strike and push the agenda by force.

According to Putin, there is no war, the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army is a consequence of the Occident decisions. For many years, Poland has Ukrainian minority in its territory. Despite all the problems between Poland and Ukraine in the past, both countries are allies.

They are partners in many fields. Today, Poland is the main country which can help Ukraine in the actual situation. That’s why immigration increased very quickly, and Poland must deal with it.

We can wonder how Poland deals with the Ukraine war. To understand the whole situation, we need to explain the historical link between Ukraine and Poland. Then we will talk about the Ukraine war origins.

Finally, we will mention the consequences of this war on Poland, and some solutions founded by the country to manage the situation

PART 1

HISTORICAL AND MODERN LINK BETWEEN UKRAINE AND POLAND

CHAPTER 1

BEFORE THE WORLD WAR

Ukraine and Poland are strategic partners, but this relationship is difficult because of the wounds of the past. In fact, the two countries have suffered from historical conflicts, like during the Second World War.

Despite, the two countries having wide-ranging and shared interests, that’s why they are always trying to forget the past. (History Still Strains Poland-Ukraine Relations, 18 November 2020).

At the end of the 10th century, Kyiv Russia (the first Ukrainian proto state) and Poland adopted Christianity as the state religion. Poland became progressively a catholic country, and Kyiv Russia an orthodox country. The relations between the two countries were not very different from the situation all around the continent during the same period.

In the 13th century, Russia was destroyed by the Mongol-Tatar invasion. After that period, Russia stopped to be an independent international actor in the world, and the Ukrainian lands fell under the domination of its neighbours: Turkey, the Golden Horde, Poland, Lithuania, Hungary, and finally Russia.

The relations between Polish and Ukrainian became more difficult, and the relationship changed, from interstates relations to different ethnic groups with a vaguely defined identity.

Lire aussi : La nation, l’identité nationale et la mémoire collective

Until the 17th century, the relations were peaceful. Most of the Ukrainian lands were under Lithuanian control and benefited from large freedom, particularly in terms of religion. In 1569, Poland and Lithuania came into a Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

After this union the Polish aristocrats were interested in the Ukrainian black soils, in the hope to expand the production of grain, later exported via the Baltic Sea to Western Europe.

In the middle of the 17th century, tensions started to rise considerably. The military movement of the Cossacks (which exercised political dominance on the Ukrainian lands) reclaimed more autonomy from the Commonwealth.

It turned into a military conflict called the Khmelnytsky uprising. Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the Cossack leader, was unable to gain independence from the Commonwealth and create a viable state. After a few years of war, the leader was obligated to ask for protection from the Russian tsar.

This union, (Pereiaslav union) led in 1654 to the progressive incorporation of the Eastern part of the Cossack «state» with Russia. At the same time, the rest of Ukrainian lands were under the control of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. At the end of the 18th century, the Cossack autonomy, within Russia, was definitively abolished.

In the second half of the 18th century, as a result, the Commonwealth was later “partitioned” by the three neighbouring countries growing in power, Prussia, Austria and Russia (in three turns: 1772, 1793 and 1795). So, the worsening situation of the Commonwealth in the 18th century led to the mentioned incorporation of those lands mostly into Russia.

The Commonwealth led to the incorporation of most of the Ukrainian lands into the Russian empire, only the most Western part was accorded to Austria. (Poland-Ukraine relations, 8 May 2022).

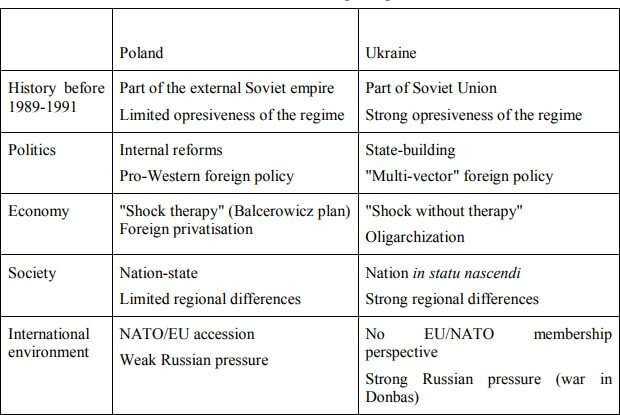

Figure 1: Poland and Ukraine: main differences. (Poland-Ukraine relations, 8 May 2022).

After that, Poland was not an independent country anymore. Nonetheless, the relations between the Polish and Ukrainian communities stayed conflictual.

The already existing different religions were accentuated by an economic and social conflict. In Russia, the Polish remained a nation of aristocrats. On the other hand, Ukrainians were mainly peasants.

According to the French historian Daniel Beauvois, the Polish-Ukrainian relations were not very different from a colonial scheme, Poles being the colonizers and Ukrainians, the colonized.

CHAPTER 2

INTERWAR PERIOD UNTIL SECOND WORLD WAR

The end of the First World War led to the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian and the Bolshevik revolution in Russia. Polish and Ukrainians hoped to create independent states.

The Polish were successful thanks to active diplomacy in Western Europe and the internal strength of the new country. It was named the Second Republic, Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth being the first. The Ukrainians were unable to realize their goal because of the internal divisions and lack of external support.

The two nations fought over Lviv and the Western Ukrainian lands, which finally joined Poland in 1918. In 1920, Poland signed an alliance treaty with the ephemeral Ukrainian People’s Republic against the Bolshevik threat.

Thanks to the Ukrainian ally, it was able to stop the expansion of communist Russia, but not to save Ukraine.

The Polish-Soviet Riga peace treaty of 1921 confirmed that a large part of the Ukrainian lands would become part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and the Eastern Halychyna and Volhynia would go to Poland.

During the period of the interwar, Poland was an independent state which was not the case with Ukraine.

This situation led to frustration among the Ukrainian population it was the majority of people living in the recent state created in South-Eastern Poland (it represents approximately fourteen per cent of the population). The problem of Poland was to develop a coherent policy to live properly with the minorities.

It wasn’t a success, that’s why the Ukrainians tended to the Soviet Union concept, which recognized the minority and accepted its cultural development. Then the Soviet government chose to apply radical measures against Ukrainians living in the USSR. In consequence, Ukrainians turned towards the extreme right, in the hope to attract Germany’s help against the Polish state.

The division of the minority and the resultant conflict kept growing. In 1929, the OUN was founded (the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists). Their principal actions were about terrorism.

The Polish state’s response was the persecution of the Ukrainian minority. (Poland-Ukraine relations, 8 May 2022). For most Ukrainians, the OUN (Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists) is still symbolising the fight for independence, especially after Russian aggression in Ukraine (in 2014).

The OUN is the Organisation of the Ukrainian Nationalists, it’s a political organisation founded in 1929 in Vienne. A union between Ukraine’s military organisation and a radical right-wing group is born in this organisation.

The OUN’s strategy to reach Ukraine’s independence was composed of violence and terrorism against abroad and international enemies, including Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Kingdom of Romania and the Soviet Union.

In 1940, the OUN split into two parts: the agest members, who support Andriy Atanasovych Melnyk in OUN-M, and the other part, there are the youngest members, more radicals supporting the OUN-B, of Bandera Stephan.

CHAPTER 3

SECOND WORLD WAR PERIOD

When the beginning of the Second World War arrived (1939), Poland’s South-Eastern part fell under the control of the Soviets as well as the Germans a few years later in 1941. The two powers ended the local elites, their goal was to start “campaigns of ethnic cleansing” which means the deportation of the Polish by the Soviets and the genocide of the Jews by the Germans.

When the end of the war was about to arrive, the different countries hoped that some places would remain parts of their state, particularly Volhynia, eastern Halychyna and the neighbouring states.

To prove the Ukrainian character of Polish living in these areas, the UPA (the part of the OUN created by Stephan Bandera) launched a campaign against these Polish. The Polish response was military defence.

The consequences were enormous, between 1943 and 1944, up to 100 000 Polish and about 10 to 20 000 Of Ukrainians. We can remember this massacre as the massacre of Volhynia, where ethnic cleansing of the Polish minority was operated by the OUN.

After the beginning of the Union Soviet invasion in June 1941, Yaroslav Stetsko, representing OUN- B declared Lviv as a Ukrainian independent state, whereas this place was under the control of Nazis. The consequences were multiple divergences between the OUN and Nazis.

After that, in 1942, the OUN-B created an army: the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army).

Between 1943 and 1944, the Polls were reinstating borders. During this operation, UPA started to lead fights against the Polish people. Historians estimated 100 000 Polish deaths in the massacre of Volhynia and Oriental Galicia. (History Still Strains Poland-Ukraine Relations, 18 November 2020).

After the second world war, UPA fought Soviet and Polish forces. During the Vistula operation in 1947, the Polish government deported 140 000 Ukrainians in Poland to pull off the support base of the UPA.

During the fight, Soviet forces killed, deported or arrested 500 000 Ukrainians, most of them were members of the UPA. During the cold war, occidental agencies including the CIA were secretly supporting OUN.

For many Poles, the representation of OUN with Bandera were war criminals, capable of atrocities, like in the Volhynia massacre in 1943. It was a fight against Poles who lived in a Ukrainian region, which was Poland’s part until 1939.

Lire aussi : La famine en Ukraine 1932-33 : les narratifs de l’Holodomor et les politiques mémorielles

About 100 000 Polish there were killed by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. This army fought against the Third Reich and the USSR during World War II.

This massacre was qualified as genocide, in 2016 by the Polish parliament. This vote, which remained anonymous, angered Kyiv. Ukraine considered the events in the context of a war, in which crimes were committed on both sides. (History Still Strains Poland-Ukraine Relations, 18 November 2020).

This conflict had little influence on Halychyna and Volhynia. These areas were attached to Soviet Ukraine, decided by the “Big Three », which is the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain.

After the agreement between the Soviet and Polish authorities, a lot of these people were repatriated to USRR, and at the same time, the Polish from Soviet Ukraine came to Poland.

Nonetheless, a part of the Ukrainians refused to leave their native lands, but their presence was known as a threat to the communist regime. In 1947, during the Vistula operation and under the pretext of eliminating all the remains of UPA in Poland, 146 thousand Ukrainians were deported to old German territories, attached to Poland.

They were dispersed to help their assimilation. Nonetheless, the Ukrainian minority was persecuted until the end of 1980 by the communists. (Poland-Ukraine relations, 8 May 2022).

CHAPTER 4

THE CURRENT INTER-COUNTRY RELATIONS

Despite this history, Poland never stops supporting Ukraine’s European inspiration. According to a 2017 Poll survey, eighty-seven per cent of Poles consider Ukraine a European country, and this percentage is far higher than all other countries in the EU.

Poland and Ukraine remain key trade partners for each other. The two countries share many common positions, especially about the Russian gas pipeline, both countries are against it. On the other hand, Ukrainians constitute Poland’s largest minority group.

The problem is that controversies over the past continue to slow down the two countries in many areas of cooperation.

“During Ukrainian-Polish meetings, 80% of the discussions were dedicated to historical issues as a result, there was simply no time for anything else, neither security nor trade, and not any other humanitarian issues,” said a senior Ukrainian diplomat, under the condition of anonymity.

In 2019, the new presidential elections tend to make the situation better. Poland viewed Volodymyr Zelensky’s victory as a new start for a breakthrough in relations.

Lukasz Adamski, a Polish historian and political scientist declare: “The new president came from a region not affected by the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation; his electorate also did not live in western Ukraine, this gave hope that he was more ready to compromise on historical issues than his predecessor”. (History Still Strains Poland-Ukraine Relations, 18 November 2020).

Since 2014, Poland has experienced an important inflow of immigrant workers from Ukraine.

This inflow arrived with enormous labour demand, that’s why the surge in labour supply contributed to a major part of Poland’s economic growth. Nonetheless, this contribution data is inexact, because of problems capturing immigration data in the Labor Force Survey.

To introduce Poland, we can notice that it is a converging country. The process to enter western Europe began around 1992. In The Following decades, Poland experienced rapid capital accumulation, growth in educational attainment and technology transfers. Poland’s accession to the European Union was in 2004.

Despite all these improvements, Poland remained an emigration country: 3% of the population left the country (1.2 million Polish) between 2002 and 2013. Most of the population immigrated to the United Kingdom and Ireland, they were 0.7 million in the period between 2004 and 2008. (The contribution of immigration from Ukraine to economic growth in Poland, 6 August 2021).

This situation reversed suddenly in 2014. From that year onward Poland admitted likely between one and two million immigrants from Ukraine. This wave of immigration, of an extraordinary scale in Poland’s modern records, was significant additionally from the Europe angle.

Specifically, “in 2018, one out of five first residence lets in become issued in Poland (635 000, or 20% of general permits issued in the ECU)”, and conversely “residents of Ukraine (527 000 beneficiaries, of which almost seventy- eight per cent in Poland) persisted to get hold of the highest number of allows in the EU».

Within the years 2016–2018, Poland became also the pinnacle OECD destination for brief labour immigrants. A considerable majority of Ukrainian immigrants arrived in Poland for monetary motives, and they without delay sought employment right here.

Their immigration became brought about inter alia through robust labour call for, relatively smooth short-term paintings and residence allowances in addition to the Russian aggression on Ukraine in 2014 with a resulting financial disaster there.

In comparison to migrants from Ukraine to Poland before 2014, less than 0.2 million generally brief people inside the agricultural quarter, the new immigrants were positioned predominantly in towns and sought work across an extensive spectrum of economic sectors.

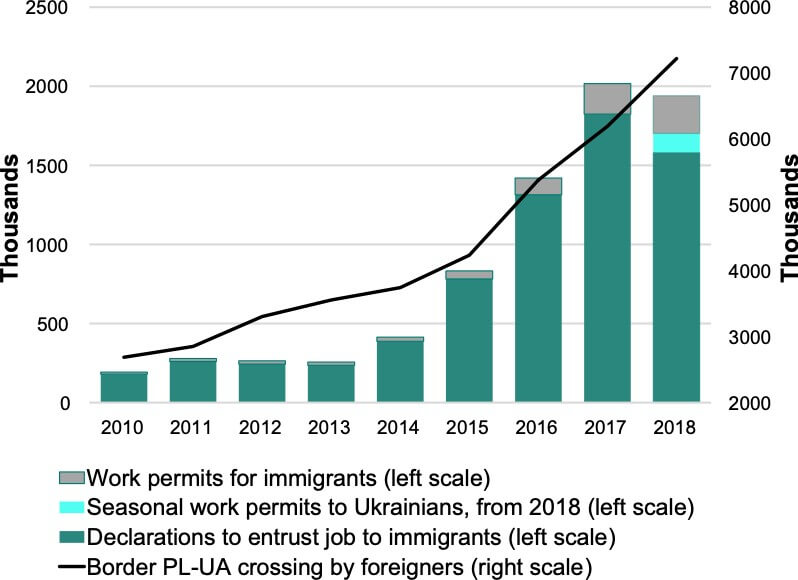

Figure 2: The size of Poland’s immigration from Ukraine, according to the ministry of labour, and polish border data. (The contribution of immigration from Ukraine to economic growth in Poland 2021).

We confirm that the increasing educational attainment of Polish workers due to the replacement of older and less educated generations by new better-educated generations provided a key contribution to overall labour supply growth from 1995 to 2018.

A smaller positive contribution was also provided by the age component, reflecting primarily population ageing, as well as the reform of early pensions in 2009 and the gradual extension of the retirement age until 2017.

A new finding of the current study pertains to the impact of the relocation of employees between occupations, related to structural changes in the economy.

In general, the impact of this factor was positive over the last 25 years but there were also isolated periods of negative changes probably related to higher labour demand for low-skilled workers. Our estimates of the labour input provided in the previous section will now be plugged into boom accounting.

As argued before, still 2014 the effect of immigration on the GDP boom in Poland remained negligible. Considering that 2014 the contribution of the labour input of immigrants swiftly grew, though, turning into a substantial part of Poland’s increased ability.

In the duration from 2013 to 2018, the contribution of the influx of Ukrainian workers to Poland’s GDP increased ranged from 0.3 pp. to 0.8 pp, so the influx of Ukrainian workers became chargeable for about 13% of monetary growth in Poland from 2013–to 2018. In truth, in 2016 and 2018 increase in the labour input of immigrants contributed to the GDP boom, more than the impact of growth within the labour input of Polish residents.

According to a longer period, the aggregate contribution of Ukrainian immigrants to Poland’s GDP growth in the whole from 1996-to 2018, was about 4%, compared to the contribution of labour input of Polish workers of about 18%.

On the other hand, when we look only at the period between 2013 and 2018, the contributions of natives and immigrants are nearly the same, it is about 13 % of total economic growth thanks to immigrant labour and almost 14 % due to natives. After 2013, the large immigration of Ukrainian citizens to Poland is an unprecedented phenomenon in Poland’s modern history. (The contribution of immigration from Ukraine to economic growth in Poland, 6 August 2021).

Nowadays, Poland and Ukraine have largely overcome their historical differences. They succeed to limit their impact on their relationship.

Thanks to them, other countries benefit from this “union”, for example, the Hungry and its neighbours benefitted from the Trianon treaty in 1919. The historical past between Ukraine and Poland was not an obstacle to their collaboration. In fact, in 1990 the Polish Senate condemned the «Vistula» massacre. Poland didn’t pay attention to historical issues. In 1997, the presidents of Poland and Ukraine adopted a new declaration to reconcile.

It’s calling both countries to «remember the past, but to think about the future». However, Ukraine has never really asked for forgiveness for the Volhynia tragedy, that point is still dividing both countries. (Poland- Ukraine relations, 8 May 2022).